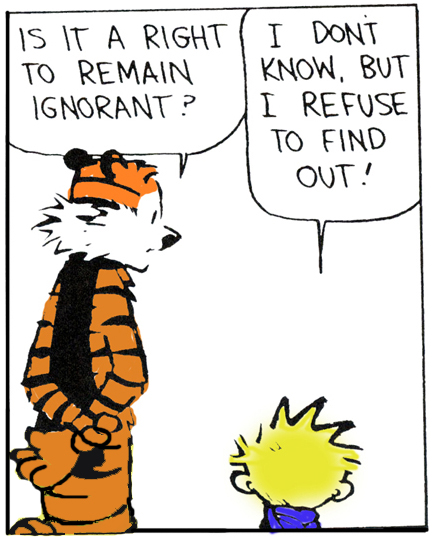

Every time there is a controversy about a movie, this topic arises again: Can you have a valid opinion about a movie you haven’t seen? The answer is mostly no — which should be obvious, but I guess it isn’t.

Every time there is a controversy about a movie, this topic arises again: Can you have a valid opinion about a movie you haven’t seen? The answer is mostly no — which should be obvious, but I guess it isn’t.

The only way you can form an intelligent opinion on a film without seeing it is if you’re basing your opinion on elements of the movie that are factual and not subject to interpretation — who the actors and filmmakers are, how many F-words it has, things like that.

For example, maybe you don’t like movies set in the Old West. If a movie is set in the Old West, that is a matter of fact, not opinion, and you can easily find it out from watching the ads or reading the reviews. Armed with that knowledge, you can determine whether you would consider it a “good” movie or a “bad” movie (with the goodness or badness here determined by that specific criterion).

Or maybe it’s the objectionable content that helps you decide. Several websites count and list the instances of profanity, nudity, sexual activity, and violence in movies, and you can use that information — all of it more or less quantifiable and not subject to much dispute — to form an opinion on whether the movie is right for you.

But when we get to a movie’s theme, or its message, or its point, now we’re talking about interpretations, and those can vary from person to person. If you and I watch a movie and count the F-words, we’re going to come up with the same number (assuming we don’t miss any). But we could watch the same movie and come out with entirely different interpretations of what its message was.

The only way to form a valid opinion on a movie’s point, message, or theme is to watch it. Period. You can read all the reviews and essays in the world, but all that does is educate you on how others interpreted it. (And what if they didn’t see it, either, but are merely going off what someone else said?) At best, you’d be parroting others’ opinions. At worst, your opinion would look foolish and off-base to people who have seen the movie.

(I ran into this recently when a reader took me to task for recommending “Lars and the Real Girl,” about a guy who falls in love with a rubber sex doll. She was going off that one-line description and concluded it must be a “bad” [i.e., unwholesome] movie — when in fact the film is utterly wholesome and sweet, with no sexual content shown or implied. People who have seen the movie would laugh at her clueless opinion of it.)

Granted, there are plenty of movies where “interpretation” doesn’t matter much because the films are shallow. You and I might have different opinions on the entertainment value of “Daddy Day Camp,” but our understanding of what the film’s “message” is probably wouldn’t differ much. In a lot of cases, the message is obvious, and the film hits us over the head with it.

But for more thoughtful films, interpretations can vary wildly. This came up quite a bit two years ago, when “Brokeback Mountain” was released and people who hadn’t seen it had all kinds of hissy fits about its message. And now this matter of people decrying the messages of films they haven’t seen arises again with “The Golden Compass.”

Many religious people have become concerned about this film because it is based on a trilogy of books that can be viewed as having an anti-religion message. The author, Philip Pullman, is a self-described atheist. People are worried because while the anti-religion message has been toned down for the movie version, it might inspire kids to read the books, and thus succumb to the evils of atheism.

I haven’t read the books, so I can’t comment on their message. (See how that works?) But I do know that while Pullman may be openly atheistic and may indeed have written the books to present an anti-religion message, that doesn’t necessarily mean that’s the message readers will take away from them. The whole thing is allegorical, of course, and allegories are open to any number of interpretations.

The best thing for concerned Christian parents would be to read the books themselves and determine whether they’re suitable for their children. If you think the anti-religion message is plain as day and you’re convinced your child would have the same understanding of it, then don’t let him read it — or better yet, do let him read it, then discuss it with him. Find out what he thought the author was trying to say. It could be a great teaching moment: “The author believes there is no God. What do you think about that? Why do you think some people don’t believe in God?” I can’t imagine a child’s belief in God being shaken simply by the realization that some authors are atheists.

As for the movie (which I have seen), while there are certainly some parallels to be drawn between the magical fascists and the Catholic Church, the whole thing strikes me more as anti-authority-in-general. It’s like a million other kids stories where young people fight against the Dark Side, or Voldemort, or the Wicked Witch, or whatever else. All of those evil institutions could be stand-ins for any number of real-life authorities — church, government, school, etc. The message I get from “The Golden Compass” as a film is that you should seek knowledge and truth and not let people tell you what to think.

Ironically, we’ve got people doing exactly that with their e-mail campaigns urging the boycott of the movie. I got one forwarded to me by a Provo woman who accompanied it with this note: “Just heard about this [movie] … doubt it will make it into Utah, but the rest of you might want to spread the word.”

Her naivete would merely be amusing if she weren’t an author herself and thus presumably someone who tries to keep up with the world. To have “just heard about” the “Golden Compass” movie is funny; to assume that it’s some fringe anti-God film that no Utah theater would allow on its screens is flat-out hilarious. It means she’s ignorant on three subjects: “The Golden Compass,” the movie business in general, and movie theaters in Utah. (I promise you, there’s no Hollywood-produced movie so controversial that no theater in Utah will show it. Even Utah has arthouses and independent cinemas.)

In summary: If you want to form an opinion of a movie based on its literal content — its language, its images, and so forth — you can do that without seeing it, because those are matters of fact that can be reported impartially. Anything beyond that requires interpretation, and you gotta see it to come up with a valid opinion of your own.