It is a twisted mind that conceived “Oldboy,” and while I am frightened to know that imaginations this macabre exist in the world, I am delighted that they have been set toward making movies, as opposed to, say, running for public office.

“Oldboy” is about a man named Dae-su Oh (Min-sik Choi) who is kidnapped and imprisoned by anonymous captors for 15 years, kept in a large-ish room with a bed, bathroom facilities and a television. On TV, he sees that his wife has been killed and that he — believed by everyone to have simply disappeared or run away — has been framed for the murder. He’s not tortured or mistreated in any way; he’s simply held prisoner, food delivered on a tray through a slot in the door, so that he has no direct contact with the outside world.

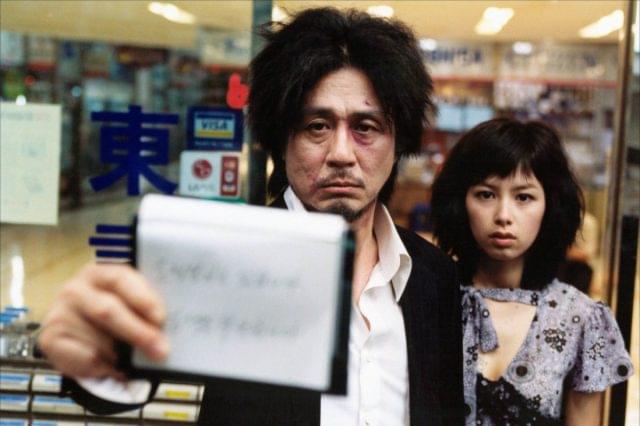

Dae-su is released just as suddenly as he was taken, dropped back into the world as a fugitive, a ghost and a nobody. He is given clothes, money and a cellphone, the latter item used by his captor to call and taunt him. Like all good unseen tormentors, he speaks in riddles, hinting at his identity and about his reasons for imprisoning Dae-su.

Then Dae-su decides to seek revenge.

Here, for the next hour, the film becomes a deviously funny, outlandishly exciting ride, snappy, thrilling and violent. Dae-su trained himself to fight while imprisoned and has emerged something of a superhero, albeit one with an agenda. Aided by a sushi waitress (Hye-jeong Kang) who takes pity on him and who also becomes his lover, he learns who imprisoned him, but then he must determine why — and even then, it’s not enough. “Seeking revenge has become a part of me,” he says.

If Quentin Tarantino were Korean, he would be Chan-wook Park, the man who directed “Oldboy” and co-wrote its screenplay (with Jo-yun Hwang and Chun-hyeong Lim). His use of urgent, intense, stylish music is certainly Tarantino-esque, and his gallows humor and fondness for violence are exemplary. (Of course Tarantino himself was inspired by the martial-arts films of East Asia, so perhaps he and Park are drawing from some of the same influences.) I note the scene where a man’s teeth have been removed as a means of getting him to reveal what he knows. His speech is garbled now, so subtitles are provided — but they’re in Korean, the language of the film, so his subtitles have to be subtitled. That’s comedy, friends. Dark, gory comedy.

Park also achieves something masterful in a scene where Dae-su fights a dozen or so henchmen in a dank corridor, shot all in one two-minute take, with no cutting away. It’s brilliantly, messily choreographed, and the longer it goes, the more amazing it is.

You will also never forget the scene in which Dae-su eats a live squid in order to make a point.

The film culminates in a grand, operatic finale full of shocking twists, and it probably is dragged out a little too long (which I guess is partly why it reminds me of an opera, but that’s neither here nor there). But there is a singular vision at work here, a mind full of imagination and cleverness, and a sharp skill for storytelling. The movie is dark, mad and haunting, and wonderfully so.

B+ (1 hr., 59 min.; Korean with subtitles; )