In 1984, Hollywood discovered that the kids on the streets were doing something called “breakdancing,” and the studio executives knew just what to do: rush out a series of hastily produced movies to cynically capitalize on the trend before it faded. Breakin’ came out in May of that year, followed by Beat Street in June, and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo in December — just eight months after its predecessor. For a movie to go from concept to finished product in only eight months is extraordinary, but Breakin’ 2 does not suffer from the sped-up schedule. It is every bit as bad as it would have been if they’d spent years on it.

I approached the film somewhat cautiously, as I had not seen Breakin’ and feared I would be hopelessly lost. Unfortunately, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo does not begin with a recap of the first movie’s plot, the way sequels like Superman II: Electric Boogaloo and Friday the 13th II: Electric Boogaloo do. I was left on my own to figure out who these complex characters were, and what their relationships were, and why they wore their leggings so tight.

Like all of your best urban street-dancing movies, Breakin’ 2 was produced and directed by old white Jewish men. Our heroine is Kelly, played by a woman named Lucinda Dickey, which is much funnier if you pronounce it Loose-in-da Dickey. Kelly is a young dancer who has returned to her rich parents’ WASP-ville mansion after finishing a professional gig elsewhere. Her Dad (John Christy Ewing) wants her to go to Princeton, but Kelly just wants to dance! And after seeing her dance, you’ll agree: She should go to Princeton.

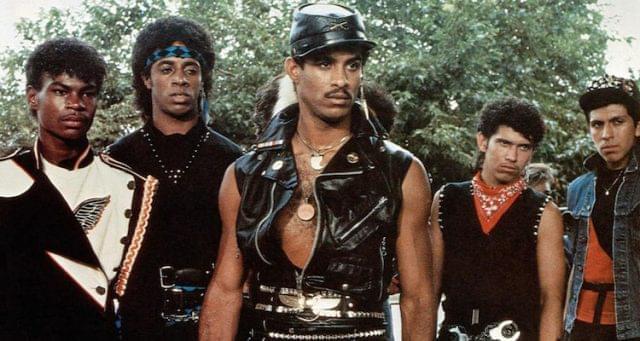

Kelly soon drives to the ‘hood to visit her old friends Ozone and Turbo, played by people named Adolfo “Shabba-Doo” Quinones and Michael “Boogaloo Shrimp” Chambers. (I guess when you show up at Central Casting calling yourself Shabba-Doo and Boogaloo Shrimp, what else are you going to do besides breakdancing movies? King Lear?) Kelly is greeted by all the neighborhood kids like some kind of spandexed Messiah, and they lead her down the street to Miracles, the community center where they now hang out. This happens as part of a huge production number featuring the film’s title song (in French it’s “Boogaloo Électrique”), which contains such explanatory lyrics as these:

We can teach you all too, ’cause we know what to do.

We’re all gonna take a walk on the avenue.

And take a walk on the avenue they do! With the guys in high-waisted harem pants, jheri curls, and oily, pencil-thin mustaches, and the girls in too-tight leggings and yearbook-photo frizzy hair, about a hundred of the street kids boogie down the street to Miracles. If this happened in real life, it would be terrifying. I don’t care what race they are or what part of town it is, if a hundred people came lurching convulsively toward me on a city street, I would make electric boogaloo in my pants.

It turns out that Miracles is in danger of being closed down. The building needs $200,000 in repairs to make it safe, and an evil white land developer named Douglas (Peter MacLean) plans to buy the property from the city, raze Miracles, and put up a shopping center. The kids must band together to put on a show to raise enough money to save the center and stop gentrification! Kelly’s dad, who it turns out is racist, could easily donate the money, but he refuses to do so on the grounds that “I know what you people do with money.” That’s a touchy subject, but let’s be honest. We all know what “those people” do when you give them money. They go out and spend it all on contractors who will bring their community centers up to code, taking into account new regulations concerning earthquake safety, repaint the centers’ exteriors to reflect neighborhood ordinances, and seek attorneys willing to work pro bono to help register them as non-profit organizations eligible for tax exemptions. Oh, and crack.

From this description it may be apparent that Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo is actually a throwback to the musicals that were popular during the Great Depression. Like those films, Electric Boogaloo has stock characters and many dance sequences, it’s about people putting on a show to save a building, and audiences are liable to suffer a great depression when they watch it.

What’s noteworthy is that while the standard practice is to hire performers who are better at dancing than they are at acting, the makers of Breakin’ 2 chose to hire performers who are better at neither. You hear them overact some simple bit of dialogue, and you think, “I’ll bet they’re better at dancing.” Then you see them dance, and you think, “Huh. Weird.” The dancing is usually the saving grace of a film like this; here, the moves are no better than you could have seen on any playground or street corner in urban America in 1984, or middle America in 1989. Adolfo “Shabba-Doo” Quinones and Michael “Boogaloo Shrimp” Chambers are pretty good, but what about the other famous breakdancers of the day? Was there no room in the film for Billy “Cocoa Puffs” Thompson or Raymond “Shibbity-Shibbity-Shoing” MacDonald? What about Raoul “Chicken Fingers” Ramirez and Stevie “Lunch Buffet” Lincoln? Where’s Johnny “Blibbity-Bling” Jones? I mean, honestly.

The kids eventually get the best of Douglas the evil land developer, then proceed with their show, even though the city council already told them it was too late to come up with the $200,000. Ozone appears on a live news broadcast to urge people to attend the festivities, saying, “There’s gonna be dancing and juggling — the whole works!” It’s a little sad that Ozone is so starved for amusement that he believes the entire spectrum of entertainment options can be summarized by “dancing and juggling,” but I guess that’s how it is in the ‘hood.

In the end, Kelly’s dad realizes how important dancing is to her and accepts his daughter’s ambitious dream of working for free at a community center. He donates the last $50,000 needed to save Miracles, and they all live happily ever after. Yes, the film is bad. But I appreciate its inspiring message that no matter how dire things get, if you and your neighbors will rally together for a common cause, then eventually a white guy with money will come in and save you. We would all do well to remember that in our daily lives.

— Film.com