The NRA is right about one thing. Movies do affect the way we think. Now, I don’t mean that violent entertainment is a major cause of real-life violence (though it’s naïve to think it has no effect). I’m not even sure the NRA believes that argument, at least not beyond its usefulness as a distraction from other issues — like, say, how the NRA’s dedication to flooding the country with guns without a corresponding flood of gun-safety training and education might share some of the blame.

What I mean is that our worldview is shaped by the things we see in fiction, especially when it comes to things with which we have no personal experience. Those of us who have never been doctors, cops, or lawyers assume that there’s some authenticity to the way those professions are depicted in movies and TV — if not in the details of the stories (which we understand are fictional) then at least with regard to the terminology the people use and the protocols they follow.

In principle, there’s nothing wrong with learning about the world from fiction. That is, after all, one of the great uses of literature: to introduce us to people, things, and places we haven’t experienced firsthand. Ideally, this knowledge is enhanced and refined by the real-life information we glean from news stories, documentaries, and whatever personal experiences we might have. That is to say, we let the things we learn about politicians and police officers in the newspapers and in our daily lives color — and where necessary, correct — the impressions we get from fiction.

Where we run into trouble is when something happens in real life that is unfamiliar to our experience, but that has been fictionally portrayed over and over again. Very few of us have any direct experience with bank robberies, either as perpetrators or as witnesses. So if we ever do find ourselves in a bank as it’s being robbed, all we’re going to know about how to react and what to expect is what we’ve learned from movies — which is a lot, because bank robberies are an exceedingly common plot device.

Likewise, while the number of gun-related injuries and deaths in America is alarming, the vast majority of us, statistically speaking, have not been witnesses to or victims of it. But the scenario of “gunman opens fire in a public place” pops up constantly in TV and movies. The result is that when it happens in real life, people expect it to play out the way it does in movies: because that’s our only frame of reference.

After the shooting in the Aurora, Colo., movie theater last July, there was a common response along these lines: “If only a good citizen with a gun had been there to stop him!” Why? In part, because in movies, that’s how it goes down. The hero — whether he’s an everyday joe, a cop, or a costumed vigilante — usually takes the perp out. But in real life, a good citizen with a gun shooting at the killer in a dark, smoky, chaotic movie theater would have been much more likely to hit an innocent bystander. Someone with training in this sort of thing (an off-duty police officer, for example) might have done better (and would have been trained not to fire unless he had a clear shot). But not the average person, no matter how well-intentioned. Buying a gun does not automatically endow the purchaser with excellent marksmanship and steady nerves in high-pressure situations.

The idea that mass shootings mean MORE people should carry guns, to defend themselves and others against future shootings, is not based on reality. It is based on movies. How many movies have you seen where an ordinary person becomes an awesome action hero when trouble breaks out, executing split-second plans, leaping through windows, and shooting bad guys when the need arises? I’ll give you a hint: You’ve seen a lot of them. And it’s fun to fantasize about what you would do in a crisis like that. We all have daydreams about bravely rescuing hostages from madmen, or outmaneuvering a criminal bent on harming us.

But in real life, unless the armed bystander is calm, rational, and has good aim (or is very lucky), he or she isn’t going to save the day. In real life, it’s not easy to hit a moving target. In real life, the prospect of shooting another human being — even one who is in the act of harming others — is daunting and terrifying. Which is at it should be! We SHOULD recoil at the thought of taking a life! We SHOULD want to exercise every other option before resorting to that one! It’s what makes us civilized. This attitude of “Well, if everybody is armed, you can just shoot whoever acts up” is decidedly uncivilized.

Movies show people firing bullets into one another without showing the aftermath. I don’t mean the part where the bad guy dies in a pool of his own blood and we are relieved to see him go. I mean the part where the person who shot him, no matter how justified he or she was in doing so, has to live with that forever. I mean the psychological trauma of taking a life, or even just of being in a life-or-death situation. That sort of thing messes you up. But you wouldn’t know it from movies.

In movies, if the shooting was justified, that’s the end of it. Guy opens fire in a coffee shop; a civilian returns fire and kills him; the end. There’s no paperwork, no legal inquiry, no second-guessing, no nightmares. Also, he never misses the bad guy and hits someone else, or just misses altogether and gets himself killed. And the cops never arrive in the middle of the fracas, see the hero wielding a gun, and mistake him for the bad guy.

In movies, things play out the way they do in the NRA’s fantasies. Or, more precisely, the reverse: the NRA’s fantasies are based on what they’ve seen in movies.

• • •

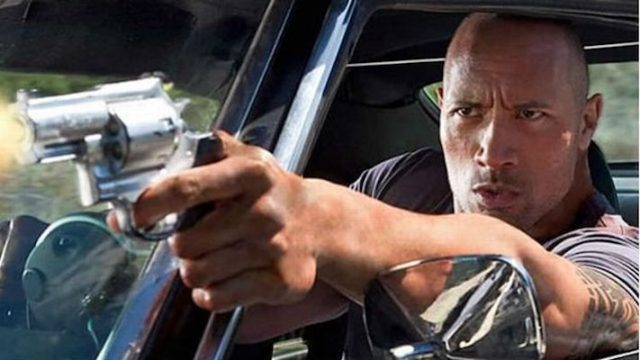

Dwayne Johnson’s new film “Snitch” provides a good example of Hollywood’s cavalier attitude toward firearms. Johnson plays a man who is emphatically a Regular Guy who goes undercover to entrap some drug dealers and thereby save his son from a prison sentence. (It makes sense in the movie.) (Well, kind of.) When things get hairier than he expected and he feels the needs to shun official help from the DEA and go rogue, he buys a gun. We see him at the gun store, looking intently at the merchandise. We understand that this is new territory for him. He has never done this before.

What we don’t see is any indication that he knows how to handle a gun. There’s no suggestion that he’s ever held a gun in his life. We don’t see him at target practice. We don’t see him learning the basic care and handling of a firearm. Yet when the time comes … in the middle of a high-speed chase … while he’s driving a semi truck … he shoots an enemy through the window of the car speeding along next to him. You know, like you do.

This is classic movie logic: GUN = PROTECTION. The crucial middle steps are omitted. What’s scary is that we’ve unconsciously adopted this inaccurate view — and, worse, that some of us want to use it as the basis for public policy. Wayne LaPierre, the executive vice president of the NRA, is famous for this declaration: “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” Like most bumper sticker wisdom, this is nonsense. It would be more accurate for LaPierre to say: “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy — sober-minded, with steady nerves, who has had sufficient training and practice — with a gun.” But that’s not as catchy.

Gun ownership is a right in the United States, but it is also a responsibility. Too many people (including too many people who own guns) forget the second part. It’s embedded in our cultural DNA: guns are all-purpose solutions to myriad problems, and anybody who picks one up can probably shoot a villain with it accurately and without consequence. We have fetishized guns — and that’s something Hollywood and the NRA can share the blame for.

— Film.com