The Jackie Robinson biopic “42″ made headlines for a couple of reasons when it hit theaters earlier this month. One was its box office haul of $27.3 million, which is the best debut ever for a baseball movie. Almost as widely reported yet perhaps more revealing: it earned a rare A+ CinemaScore from audiences.

CinemaScore results have become as much a part of box office reports as the dollar amounts. Studios also use them in marketing materials, quoting the CinemaScore in commercials and on DVD and Blu-ray packaging. But what is CinemaScore? Where did it come from? What does it want from us? Can it hurt us? Does it pose a threat to our children? I will answer all of these questions and tell you what to think.

Poll dancing

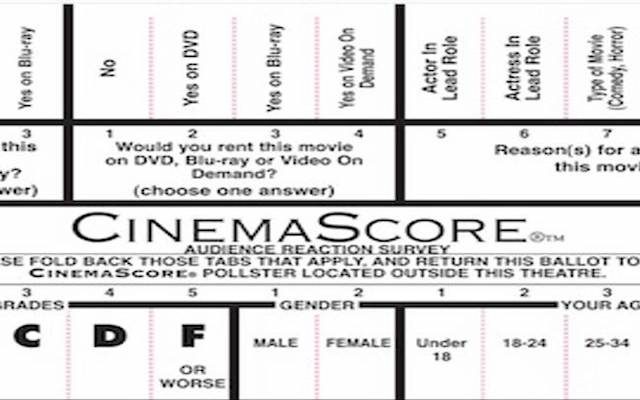

Founded in 1978, CinemaScore sends pollsters to theaters in a handful of U.S. and Canadian cities every Friday night to get audience members’ reactions to new wide releases. Viewers assign a grade of A (“or better”), B, C, D, or F (“or worse”) — no pluses or minuses — and CinemaScore calculates an average. They ask a few demographic questions, too, and stuff like “Would you buy this movie on DVD?” The results are made available to the studios, which pay “thousands of dollars a year” (according to the Los Angeles Times) for access to the data.

CinemaScore is primarily an industry tool. The company didn’t really even have a website until last year, and even now only paid subscribers have access to grades going back further than three months. But many moviegoers nowadays are interested not just in the films themselves but in the box office, marketing, critical consensus, and public reaction — hence the increasing prominence of CinemaScore in showbiz reports. In a way, we’re all industry tools.

Most movies get a CinemaScore of B or higher, which means most CinemaScores don’t provoke any discussion. But an A+ is rare: fewer than 60 movies have ever earned it. There must be some fudging involved, since “A+” isn’t actually one of the choices on the ballot. I don’t know what ratio of A to non-A grades a movie has to have for its average to be A+. At any rate, it’s rare, and an F is even rarer: only eight films have earned that distinction, and not one of them starred Martin Lawrence, so right away you know something is fishy.

Those extremes are what bring out the baffled or outraged Internet commentary — usually along the lines of “That crappy ‘Here Comes the Boom’ got an A?!” or “The brilliant ‘Killing Them Softly’ got an F?!” Or: The “Evil Dead” remake only got a C+! “Haywire” got a D+! “G.I. Joe: Retaliation” got an A-?! “Alex Cross” got an A?!

The tendency is to break into another chorus of that popular song, “Moviegoing Audiences Are Dumb and Don’t Like Films That Are Challenging or Different.” But while that may be true enough in general, it’s not fair to cite CinemaScore as evidence of it.

That’s because CinemaScore isn’t a gauge of how general audiences feel about a movie, it’s a gauge of how successful the marketing was. It’s also a reflection of the mindset of the modern moviegoer.

Stay with me here.

Every movie has an Audience. By “Audience” I mean people who would enjoy that movie if they saw it. Not everybody sitting in the audience is necessarily part of the Audience, you know? For a movie like “The Avengers,” the Audience is vast. It includes the millions who saw it and liked it, as well as the millions more who didn’t see it but would have liked it if they had. For other movies, the Audience is smaller. The “Twilight” movies appealed almost exclusively to fans of the books — a large number of people, but a narrow demographic. They were its Audience, and heaven help anyone else who wandered into a screening.

It’s the job of the marketing department to figure out who the movie’s Audience is; target those people; and get them into the theater. Marketing’s duty is to play matchmaker. Every movie has an Audience, and every Audience has many movies. The trick is to get them hooked up in the right combination.

Whence bad CinemaScores?

So when a film gets a devastatingly low score, like last year’s F’s for “Killing Them Softly” and “The Devil Inside,” does that mean those movies are terrible? No. Or not necessarily, anyway. All it really means is that the movie wasn’t seen by its Audience. It was seen by other people — the wrong people. The people who would like “The Devil Inside,” whoever those people might be1, did not go to the theater.

Sometimes the marketing department had the right idea about who would love the movie and simply failed to reach those people. But more often, a disappointing CinemaScore is the result of misleading or misguided marketing. You brought people to the theater by promising them one thing, and when the movie didn’t deliver that, they were understandably disappointed.

“Drive” is a prime example. The advertising made it look like a slightly artsier “Fast and the Furious” sort of underworld thriller, with exciting car chases and Ryan Gosling, who in a parallel universe is Paul Walker. No doubt many of the people who saw it on opening night were drawn to it because of that. But “Drive” is not that movie. It’s much more serious and brooding, and it’s punctuated by shocking moments of extreme violence.

The CinemaScore for “Drive”: C-. Compare that with its overwhelmingly positive reviews and the fervent fan base it developed. Obviously there were people — a lot of people — who loved “Drive,” but on opening night, they were outnumbered by people who didn’t. If you promise me pizza, and I have my heart set on pizza, and I come over expecting pizza, and then you give me something that looks like pizza but tastes like beef stew — well, there’s a good chance I’ll be disappointed in the evening. And that may be true even if I normally like the taste of beef stew!

(Important note: I enjoy beef stew.)

George Clooney has been a victim of this at least twice, with an F for “Solaris” and a D- for “The American.” Viewers were anticipating a sci-fi adventure and a spy thriller, respectively, not slow-moving, contemplative dramas with little action. Sometimes when a movie is hard to pin down to an easily defined genre, the marketing department gives up, lies about it, and hopes for the best. And, to be fair to the marketers, sometimes people see George Clooney! Science-fiction! and make up their minds without looking any further.

“Killing Them Softly” was sold as a high-spirited, darkly comic crime caper with badass stars like Brad Pitt, Ray Liotta, and Tony Soprano. It was those things — but it was also a scathing commentary on the American government’s reaction to the banking crisis. Audiences tend to be tough on movies that criticize America anyway, but especially when they’re blindsided by it.

As for “Evil Dead,” I can’t help but think that the bold advertising tagline — “The Most Terrifying Film You Will Ever Experience” — worked against it. That’s a serious claim to make, especially for a movie that doesn’t actually even try to be “terrifying” very often. Bloody, yes. Scary, not particularly. If audiences had gone in expecting “bloodiest” rather than “most terrifying,” I suspect that C+ CinemaScore would have been higher.

Who likes it, and why?

So that accounts for some of the low CinemaScores. Where do the surprisingly high grades come from? Here it’s important to remember that CinemaScore does its surveys on opening night. Not the whole weekend — just opening night. People who see a film on opening night are, by and large, the people who are looking forward to it and expecting to like it. They believe — either through the advertising they’ve seen or through other factors (the franchise it’s part of, the star, etc.) — that this is a movie for them. They believe they are the Audience.

Now, if the marketing department has done its job properly, then opening-night crowds are indeed the Audience for it. You’ll have some other people there too — the semi-curious, the nothing-else-to-do, the first-choice-was-sold-out-so-we-went-with-this — and they may or may not turn out to be the Audience. But if the theaters are mostly full of people who are the Audience, those outliers won’t matter, statistically speaking.

This is why almost every CinemaScore is a B or higher. The people seeing a film on opening night are already emotionally invested. Normal people don’t go to a movie on opening night with an attitude of, “All right, movie. Try to impress me.” That’s more of a second-weekend thing, after hearing positive reports from the first weekend.

“Breaking Dawn: Part 2″ got an A. Well, of course it did. Who went to that movie on opening night other than people who loved the franchise and were dying to see the final chapter? The same goes for “The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey” (CinemaScore: A) and most Tyler Perry movies. The people who are most eager to see a film are the people who are most likely to judge it uncritically, to disregard any flaws it may have. That’s human nature.

“42″ promised viewers an inspiring, uncomplicated, feel-good, soft-PG-13 story about baseball and race relations, based on a true story and released at the beginning of baseball season. It doesn’t matter how “good” it is (which is subjective), there’s no denying it delivered exactly what it said it would.

It may be instructive to look at the list of movies that have gotten A+ CinemaScores. (That list is from August 2011 and is missing a few recent entries.) They include some categories that aren’t surprising: movies that went on to win Best Picture (“Titanic,” “Schindler’s List,” “Gandhi,” “Driving Miss Daisy,” “Dances with Wolves,” “Forrest Gump,” “The King’s Speech,” and “Argo”); animated offerings from Pixar or Disney (“Beauty and the Beast,” “Aladdin,” “The Lion King,” “The Incredibles,” “Tangled,” “Toy Story 2,” “Monsters Inc.,” “Mulan,” and “Up”); and inspiring stories about teachers and mentors (“Finding Forrester,” “Lean on Me,” “Mr. Holland’s Opus,” “Music of the Heart”).

But also heavily represented is a type of movie that I wouldn’t have guessed but which makes perfect sense now that I think about it: movies about overcoming racism. “The Blind Side,” “Driving Miss Daisy,” “A Dry White Season,” “The Help,” “Ray,” “Remember the Titans,” and now “42″ all got A+ CinemaScores. Again, while you can debate the artistic merits of these movies, it’s easy to imagine opening-night crowds floating out of the theaters on clouds of warm fuzziness, having received exactly what they came for.

Over at HSXSanity, Roger Moore analyzed data from the last few years and found that CinemaScores are fairly accurate in predicting how a movie will perform at the box office in the long run. That makes it useful to people in the industry. As for the rest of us, CinemaScore reveals nothing about a movie’s quality, or even really whether the average moviegoer likes it. What it does offer, though, is a fascinating glimpse into the sociology of moviegoing.

— Film.com