People who have watched Steven Seagal movies — “victims,” as they are known — have often wondered how the humorless, dough-faced goon managed to make so many films when nearly all of them were terrible. It was natural to assume that Seagal’s first movie must have been good, and that his continued employment was the result of leftover goodwill from that initial success, in the same way that we keep putting up with Kate Hudson just because of “Almost Famous,” or Texas just because of Austin.

But as it turns out, that’s not the case. Seagal’s first movie, “Above the Law,” is bad, too. Not as bad as “On Deadly Ground” or “Half Past Dead,” perhaps, but what is? And if the first Seagal movie was idiotic, how was he ever allowed to make a second one, let alone 50 more after that? The mystery endures, the answer as remote and unknowable and dense and smelly as Seagal himself.

“Above the Law” begins with Seagal’s character, Nico Toscani, bragging to us about how he went to the Far East to study martial arts with the masters when he was only 17, before being recruited by the CIA when he was only 22. Not that it’s a big deal or anything. He’s just telling us. Recruited by the CIA at 22?? Why, yes, I suppose that is a little young, ha ha — really, Nico is embarrassed to even talk about it, it was so long ago! Stop, Nico is blushing now!

As a new CIA recruit in 1973, Nico witnesses another CIA operative, Zagon (Henry Silva), torturing the crap out of some informant in Vietnam. Nico, trying to stop the savagery — Nico is anti-savagery; just go with it — gets into a fight with Zagon that ends with Nico backing down, outmatched. Nico cannot abide brutality. For as the movie will soon establish, the only time cruel violence against opponents is permissible is when Nico is the one perpetrating it. A government agent who is considering stabbing an opponent with a machete or smashing an innocent bystander’s head into a wall would do well to stop and consider this question: Am I Nico? If the answer is no, then he must not proceed.

Now it is 1988. (Well, not now now. Now at this point in the movie.) Nico is a Chicago police detective with a wife and baby daughter. What did the Vietnam/CIA/Zagon vignette have to do with anything? Possibly nothing! That wouldn’t surprise us. We’ve seen prologues even more elaborate than that turn out to be wholly irrelevant. At any rate, Nico’s partner is a hot lady cop named Delores “Jacks” Jackson, played by Pam Grier in an unflattering ’80s blazer. Jacks, who will soon take a job in the D.A.’s office, has only One Week Left on the police force. She keeps mentioning this, over and over again. It’s like she WANTS to get shot.

Nico and Jacks learn, as cops in these movies tend to do, that a shipment of drugs is coming in soon. Nico had to beat up a few guys in a bar to learn this, but it was worth it, because 1) he got the information and 2) he got to beat up a few guys in a bar. Nico then does some illegal wiretapping to find out where and when the delivery will take place, while Jacks frets about doing illegal things and mentions that she only has a few days left on the job. The bust on the shipment leads to a shoot-out in which Jacks is miraculously NOT wounded, followed by the obligatory scene wherein the villains try to get away and Nico clings to the roof of their speeding car and punches through the passenger-side window and nearly strangles one of the bad guys to death, all of which is taught at the police academy.

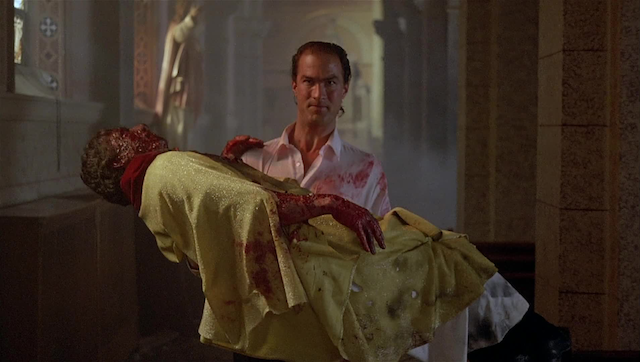

But guess what? That shipment of drugs? NOT DRUGS. It’s plastic explosives — C4, specifically, the most famous kind of plastic explosives, much more popular than C’s 1-3. And no sooner have Nico and Jacks arrested the villains and confiscated the C4 than the FBI shows up and orders them off the case. That’s fine with Jacks, who will be leaving the force in a few days anyway (did I mention that?), but not with Nico. Nico is steamed! You can tell because the vacant scowl that is always on Steven Seagal’s face looks especially scowly. He gets even angrier the next Sunday, when he’s at Mass and someone blows up the church, killing the priest and a couple others. Regardless of your feelings about organized religion, I think we can agree that blowing up a church is uncalled for (unless Nico does it, of course).

The movie’s nearly half-over at this point, and while Nico has been told to back off a particular case, that’s only part of the Generic Cop Movie requirement. The other part is that he needs to be suspended from the force and told to hand in his badge and gun. How else is he going to catch the bad guys? Everyone knows that the bulk of all effective police work in movies is accomplished by cops who are bending the rules, breaking the law, and/or not technically allowed to be doing police work at all. Fortunately, the FBI tells Nico’s bosses about his illegal wiretapping and such — the FBI apparently just knows about this stuff, I guess — and he’s suspended. Now, at last, he can get some work done!

Here is where the plot gets very complicated. No, complicated isn’t the word I’m looking for. It’s not that the plot is complex and layered and multifaceted in a manner suggesting a strong overall vision of the master plan. It’s that a lot of random details keep getting thrown on the pile, one after another, until there is just a tall, shapeless pile of details. For example, here are some things that are given screen time but aren’t ever relevant:

– Nico was born in Sicily and has relatives who are involved with the Mafia.

– Nico went to the Far East at 17 to learn martial arts.

– There are illegal immigrants hiding in the church basement while waiting to get their papers.

– Nico can get into a fight with six guys at once, some of them armed with weapons, and he will break every one of their necks with his bare hands without breaking a sweat or changing his expression or being likable.

So the plot is “complicated” in the same way that the junk drawer next to the silverware drawer is “complicated.”

Remember Zagon, the rogue CIA dude from the prologue? He’s behind all this. The Vietnam/CIA/Zagon vignette is relevant after all! He and his men are planning to kill a U.S. Senator who’s been investigating their nefarious deeds, and the bomb at the church was meant to kill a priest who found out about the assassination plot. Zagon still has a grudge against Nico, too, even though their one interaction was 15 years ago, lasted five minutes, and didn’t actually cause Zagon any harm. It is possible that Zagon has anger issues. Then again, you’d be pretty frustrated in his current situation too: He thought he was going to pull off a nice, easy assassination — and then he happens to get investigated by the same self-righteous meathead he once tangled with on the other side of the world, who’s now coincidentally a cop in the city where the crime is to take place. That’s some seriously bad luck.

So there’s a lot of scenes of FBI agents, drug dealers, dirty CIA agents, and cops shooting one another, and an equal number of scenes of Nico punching dudes or kicking dudes in the stomach, and finally Jacks gets shot, but she’s wearing her vest so she’ll be OK. At the end, Nico condescendingly lectures one of the bad agents about how no one is “above the law,” and the surprise twist is that Nico doesn’t see the irony in this. All along we assumed the title “Above the Law” referred to Nico, but it turns out it refers to the villains, i.e., the ones who break the law but have the misfortune of not being Nico. That twist would stop being surprising in Seagal’s later movies, but in “Above the Law” it was still fresh.

— Film.com