Among the many obscure and demanding clauses in the typical recording contract is one that requires the performer, once he or she has sold a certain number of records, to star in an irredeemably crappy movie. It has ever been thus. Before movies and records were invented, popular opera singers were forced to star in bad circuses. In Elizabethan England, successful minstrels would try to get parts in Shakespeare’s famous plays, but usually wound up in one of the Bard’s lesser works, like “Forsooth! My Britches!” or “The Tragedy of King Fartsalot.”

In the modern era, everyone from The Bee Gees to Miley Cyrus has fallen victim to this practice. In some cases, the singers make movies because they have reached legitimate “star” status and are looking forward to long, prosperous careers. In other cases, there is Vanilla Ice.

As clueless as Ice may have been in 1990, he couldn’t have thought his fame would last forever. Yes, the manner in which he then rocked a mic was like that of a vandal. But surely he didn’t believe his chump-waxing prowess would retain its candle-like nature indefinitely. Surely he knew that 20 years later, children would doubt that such a thing as “Vanilla Ice” had ever existed outside their grocer’s freezer. And so, in 1991, Ice did the smart thing and demanded $2 million to star in a movie to document his fame. That movie is called “Cool As Ice.”

The lead character in “Cool As Ice” is Johnny, who is played by Vanilla Ice, who is played by Robert Van Winkle. Johnny is a very tough biker dude who, like most very tough biker dudes, rides a bright yellow motorcycle. Johnny travels in a posse consisting of himself, two African American dudes, and an African American girl, none of whom have names. In fact, Johnny himself does not have a name until the movie is half over. The filmmakers had finished 50 percent of their work before they realized their protagonist didn’t have a name, and then they just gave him the first one that popped into their heads.

Not-yet-named-Johnny and his anonymous friends are biking down a country lane one fine day when they see a pretty girl riding a horse in a pasture, separated from them by a wooden fence. Soon-to-be-called-Johnny wants to impress the equestrian with his suaveness, so he uses an invisible ramp to jump the fence on his motorcycle, landing directly in front of the terrified horse, which rears up on its hind legs and throws the girl to the ground. Exemplifying what will prove to be the film’s dominant theme, Johnny is surprised to discover that his actions have consequences. He cannot understand why the girl is angry with him. To be fair, though, the film’s second-most dominant theme is that no matter what Johnny does, the ladies love him. So you can see why he’d be confused here.

Johnny’s encounter with this girl contains the film’s first real dialogue and thus the first indication of what sort of movie we are dealing with. Here is what happens after Johnny makes her horse throw her off:

JOHNNY: Hey, you OK? (she punches him in the gut) Damn! What the hell’s wrong with you?

GIRL: What the hell’s wrong with YOU?

JOHNNY: Nothing, till now!

GIRL: Aww, did I hurt you?

JOHNNY: It’s all right, I’ll live. (she gets back on her horse) Yeah, you hit pretty good for a GIRL.

GIRL: Yeah? Well, coming from a big macho biker like yourself I’ll take that as a compliment. (she rides away)

Ah. It is THAT kind of movie. The kind of movie where the main character does something reckless that could have caused serious injury, then responds to the victim’s anger with childish belligerence, in dialogue evidently written by a ninth-grade drama student.

Later, Johnny and company are tooling through town when one of their motorcycles suffers a mishap. As luck would have it, they soon roll past a mom-and-pop motorcycle repair shop operated by Charley Cheswick from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and Blanche the dippy secretary from “Grease.” Named Roscoe and Mae, they are comical, bumbling, rustic characters, providing a contrast to Johnny and his crew, who are neither comical, bumbling, rustic, nor characters. Somehow it transpires that the group will live with Mae and Roscoe, in their eccentrically decorated house-slash-garage, until the motorcycle is fixed. That’s right — this is one of those charming bed-and-breakfast-and-motorcycle-repair-shops you’ve read about in magazines.

And guess who lives right across the street from Mae ‘n’ Roscoe’s Auto Repair and Youth Hostel? The girl that Johnny knocked off a horse earlier! Her name is Kathy (Kristin Minter), she’s a bright high-school senior with a promising college career ahead of her, and she has a preppy jerk boyfriend named Nick (John Haymes Newton). You might think a girl like this would want nothing to do with the smirking boob who spooked her horse, but that’s only because you’re fixated on outdated concepts like “reality” and “plausibility.” The fact is, Johnny’s garish wardrobe, his fake tough-guy dialect, and his inconsistent attitude toward shirt-wearing render all human females powerless to resist him. As if to prove this point, Johnny flirts with Kathy as she and Nick try to enter her house, and steals her day planner when she isn’t looking. Why, this Johnny fellow could charm the stink off a monkey!

Johnny returns to Kathy’s house later that evening to be suave some more, and possibly also to steal some more of her things, but she isn’t home. She and Nick have gone to “the Sugar Shack,” which is not a brothel but rather the local teen hangout. Kathy’s pesky little brother, Tommy (Victor DiMattia), thinks Johnny is the epitome of cool; Kathy’s dad — played by Michael Gross, also the dad on “Family Ties” — is not impressed. Rest assured, though, by the end of the film even “Family Ties” Dad will be singing Johnny’s praises. ALL HAIL JOHNNY AND HIS YELLOW MOTORCYCLE.

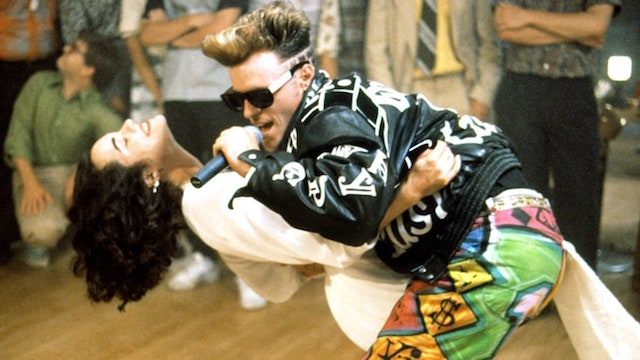

So Johnny and his nameless friends go to the Sugar Shack, where some lame “rock and roll” band is playing their “music” and boring everyone to death, and Johnny saves the day by having one of his friends scratch some records while Johnny freestyles some rap, as is the custom. Kathy flirts shamelessly and slow-dances with Johnny, right in front of Nick, then can’t understand why Nick is upset. Nick treats Kathy condescendingly, then can’t understand why Kathy thinks he’s a jerk. Robert Van Winkle changes his name to Vanilla Ice, then can’t understand why nobody takes him seriously. The cycle repeats itself.

Back at Kathy’s house, a couple of goons have shown up to shake down “Family Ties” Dad for $500,000, on account of something “Family Ties” Dad did in the past (other than “Family Ties”). FTD mistakenly believes that Johnny is associated with the goons, thus giving him one more reason to forbid Kathy from hanging out with him, as if more reasons were needed. Meanwhile, back at the Sugar Shack, Nick takes a baseball bat to Johnny’s friend’s motorcycle, and Johnny stands up to him.

Would it surprise you to learn that Johnny is a terrific fighter? As in, he doesn’t just hold his own and defend himself, but skillfully and methodically takes down Nick and his friends single-handedly? It would not surprise you to learn this? Good! Then you have been paying attention.

The next thing Johnny does that should be considered antisocial behavior but is instead received graciously is sneak into Kathy’s bedroom in the morning and wake her up by putting ice in her mouth. (Please note that I mean actual frozen water.) He gives Kathy her day planner back, and the two of them spend the day together, montage-style. Their primary activities are hanging around a construction site and riding Johnny’s motorcycle in the desert, which I guess is right next to the construction site, which I guess is right next to whatever town this all takes place in. They also have deep conversations like this one:

KATHY: What’s important to you?

JOHNNY: Being true to yourself.

Yes, it is important to Johnny that he be true to himself. One assumes this line is here as an act of self-parody, like when a character played by James Franco urges against marijuana use.

I have forgotten to mention that occasionally the film cuts back to Mae ‘n’ Roscoe’s Down-Home B&B Garage, where Johnny’s friends — who serve no purpose in the story — keep themselves occupied by dancing.

As you have probably predicted, the goons who are shaking down “Family Ties” Dad kidnap young Tommy, and FTD assumes Johnny is involved, which Kathy adamantly denies. Kathy has only known Johnny for a day and a half, during which time he has broken into her house, stolen her property, beaten up her boyfriend, frightened her horse, and demonstrated an appalling lack of fashion sense — but Kathy is sure nonetheless that Johnny could NOT be connected to anything illegal.

For his part, Johnny does nothing to clear up the misunderstanding, since he’s a rebel and being misunderstood is sort of his “thing.” Instead, he figures out where the kidnappers are holding Tommy, busts into the place on his motorcycle, saves the day, earns the respect of “Family Ties” Dad, sha-la-la-la. A celebratory rap number commences, which the FBI will tell you is how most kidnappings end.

“Cool As Ice” is 91 minutes long. But if you subtract the six-minute opening-credits sequence and the four-minute hip-hop number and four minutes of closing credits at the end, you’re left with 77 minutes of actual movie. And if you subtract from that the many, many scenes of people just dancing or rapping or riding around on fluorescent motorcycles, you’re left with about 65 minutes of movie. And if you subtract from THAT all the nonsensical dialogue, wooden acting, and extraneous characters, you’re left with -10 minutes of movie. That’s right, removing the bad parts from “Cool As Ice” actually results in a negative running time. If you leave this movie sitting next to another movie overnight, in the morning the other movie will be 10 minutes shorter than it was. That is science.

Vanilla Ice was unable to maintain his momentum, and he soon sank to Milli Vanilli levels of infamy. We should not be too quick to judge, though. To quote Shakespeare, let he among us who has never overestimated his own chump-waxing skills cast the first candle.

— Film.com