Nothing will turn a conversation awkward faster than bringing up religion. So let’s do that now! Then we can talk about politics!

It’s no exaggeration to say that the vast majority of people worldwide belong to one religion or another — about 84 percent, actually. That figure holds in the United States, too, where about 76 percent claim Christianity, another 7 percent identify with another faith, and just 16 percent are agnostic, atheist, or unaffiliated. (Another 1 percent either don’t know or didn’t answer the question. I assume they didn’t answer. I mean, if YOU don’t know what religion you are, who does?)

A vast majority of Americans also watch movies at least occasionally. And yet despite the huge role that religion and movies play in our lives, the two don’t overlap very much. Most movie characters aren’t religious unless it’s the central, defining aspect of their character, or unless they’re Irish or Italian and therefore obligated to be Catholic. Religious people in movies tend to be portrayed as kinda nutty, too — and make your jokes, but obviously that’s not true in real life. More than four-fifths of the people around you claim a religious affiliation. They can’t ALL be crazy.

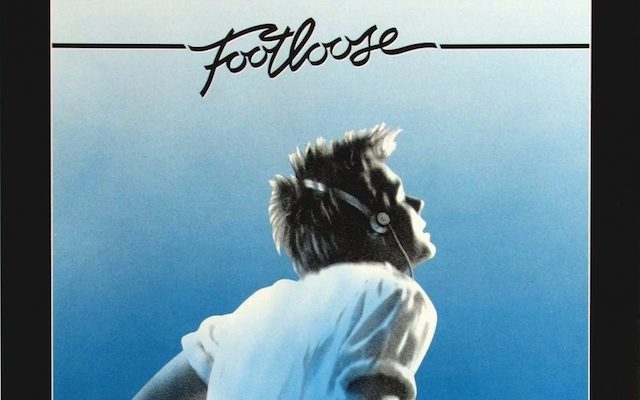

This new biweekly column, Cinemaligion (Reel Religion was too played-out), will discuss the way matters of faith and spirituality are treated in movies. Let us begin by addressing that insightful study of small-town religion, “Footloose.” Kick off your Sunday shoes and let’s go!

Many of the details of this film, about a city boy who moves to a town where public dancing is outlawed, are vague. It’s not clear what state Bomont is in (the license plates say Utah, but that’s only because the movie was filmed there), and no particular Christian denomination is singled out, either. Rev. Shaw Moore (John Lithgow) preaches at First Christian Church, which is non-denominational, i.e., not Baptist, Lutheran, Methodist, etc., but simply “Christian.” About 4 percent of Americans belong to non-denominational Christian churches like this one. These churches are not affiliated with larger, centrally organized branches of Christianity, leaving them free to adhere to whatever specific doctrines they want. The basics are the same — Jesus, the New Testament, the crucifixion, and so forth — but they can make their own local rules.

For example, they can forbid dancing. I suspect that’s why the film doesn’t get more specific about what religion these people are: There isn’t really a major Christian sect where dancing is a straight-up sin. Traditional Seventh-Day Adventists frown upon it, but they don’t seem to be kicking people out over it. Some Southern Baptist churches ban the boogie among the faithful, but it’s not central to the Southern Baptist Convention. When you hear of certain Christians not being allowed to dance, they’re probably members of an Apostolic Pentecostal faith (“holy rollers,” they’re sometimes called), which means they’re also not supposed to go to movies or wear makeup. The real-life Oklahoma town that inspired “Footloose” was led by a Pentecostal minister. You can imagine how fun that place was.

Rev. Moore doesn’t believe dancing is inherently sinful. He opposes it because it’s usually accompanied by rock ‘n’ roll music (which he disapproves of) and is often associated with alcohol, hormones, and teenage naughtiness. Many churches host well-chaperoned youth dances, which cuts down on the dirty dancing and the presence of alcohol, but Moore doesn’t support that. His real sticking point, it turns out, is that his son was killed in a car accident while driving back from one of the raucous dances. Moore’s objection isn’t so much faith-based as grief-based.

The first several scenes of “Footloose” set up Bomont as a one-dimensional hick town (“police” is pronounced “PO-lice”), and we expect Moore to be a tyrant. The locals have a cartoonishly broad reaction to Ren’s (Kevin Bacon) assertion that “Slaughterhouse Five” is “a classic.” “Maybe in another town it’s a classic,” one of them says. But notice — it’s not Moore. It’s not Moore that organizes a book-burning later on, either. It’s his most devoted followers, the bow-tied Roger (Alan Haufrect) and his wife, Eleanor (Linda MacEwen). They’re the ones who take Moore’s teachings to an extreme, further than Moore intended. If Rev. Moore is “The Simpsons”‘ Rev. Lovejoy, then Roger and Eleanor are Ned and Maude Flanders.

Surprisingly, Moore is not an unreasonable zealot. In fact, he proves to be a fairly realistic depiction of a Christian minister with teenage children. When he spots his daughter, Ariel (Lori Singer), dancing while listening to rock music at a burger joint, he doesn’t freak out. Stunned and disappointed, he does what he came there to do — give Ariel some money to buy snacks — and walks away. He doesn’t lock Ariel in the basement or go all Piper-Laurie-in-“Carrie.” (Ohh, “Carrie.” We should do that one next.) He listens to his levelheaded wife (Dianne Wiest) when she reminds him that they used to dance when they were young, too. He ultimately listens to reason and relents on the issue of prom — something his overzealous followers do not.

Notice his words at the city council meeting, when he explains why he opposes the school having a dance. I’ve emphasized certain phrases. “Even if this was not a law — which it is — I’m afraid I would have a lot of difficulty endorsing an enterprise which is as fraught with genuine peril as I believe this one to be. Besides the liquor and the drugs which always seem to accompany such an event, the thing that distresses me even more is the spiritual corruption that can be involved. These dances, and this kind of music, can be destructive.”

I believe. Always seem to accompany. Can be destructive. Though Shaw might slip into some black-and-white, hellfire-and-brimstone rhetoric in church, he knows nothing is really that clear-cut. He feels responsible for the spiritual life of the town, and as such worries about moral dangers. His concern about school dances being a hotbed of illicit drinking and teenage sexytimes is perfectly valid, as you will recall if you ever attended a school dance. He has thrown the baby out with the bathwater by getting the town to ban dancing altogether, but his original intent was motivated by genuine compassion that simply got tangled up with his grief over his son’s death.

He comes to realize this, thanks to the noble outsider who loves to dance (and drink, and smoke, and, for some reason, do gymnastics). Rev. Moore’s conclusion is that once you’ve taught your children right from wrong as best as you can, it’s up to them. “Do I hold on, or do I trust you to yourselves? To let go and hope that you understood at least some of my lessons? If we don’t start trusting our children, how will they ever become trustworthy?” He says that if the students want to hold a dance, he won’t stop them. Instead, he asks the congregation to join him in praying that the Lord will watch over the young people. To my mind, that’s true Christianity: teach, love, set a good example, pray for others, and let people live their lives. If that means everybody cuts, everybody cuts footloose, so be it.

— Cinematical