The most surprising thing about “Sausage Party” — a hard-R-rated cartoon conceived as a filthy version of “Toy Story” with food instead of playthings — is that it’s not a one-joke movie. Yes, it has sexual puns about hot dogs (all male) and buns (all female) yearning to be together, and numerous other food-related jokes of the it-practically-writes-itself variety. But it also has a story, an honest-to-goodness plot with themes and obstacles and character arcs and everything.

The least surprising thing about “Sausage Party” — which was conceived by Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg, and Jonah Hill, then written by Rogen, Goldberg, and the team of Kyle Hunter and Ariel Shaffir (“The Night Before”) — is that it relies too much on unmotivated obscenity and has an ending that screams We couldn’t think of a good ending. It’s consistently sophomoric, periodically hilarious, and peppered with minor stoner insights. (Dude, Israelis and Palestinians both love hummus! They should build on that common ground!)

Every morning at the grocery store, all of the food items greet the day by singing a song — a hymn, really — about the Great Beyond, the glorious place where food goes after “the gods” (humans) take it from the supermarket shelves. Every piece of food longs to be deemed worthy for selection, and as the song (written by Disney stalwarts Alan Menken and Glenn Slater) attests, they’re pretty sure nothing bad happens once the gods get them home.

Well — a story about sentient food that doesn’t know what humans do with food: I’m sold. Making it a commentary on religious faith ups the ante. For when a jar of honey mustard (voice of Danny McBride) is returned to the store and put back on the shelf, he brings with him a horrifying tale of what actually occurs in the Great Beyond. No one believes him, though; after all, they’ve been singing this song every day for who-knows-how-long. How could their whole religion be based on a lie?

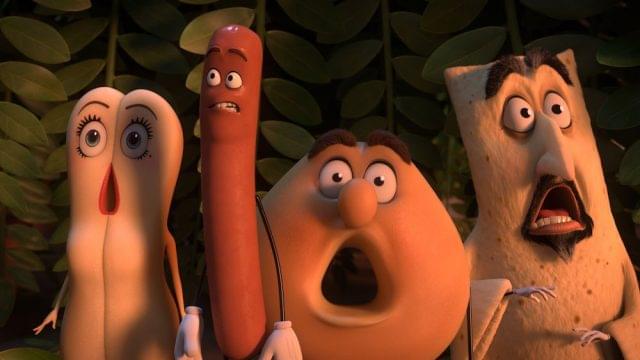

Our hero is a hot dog named (obviously) Frank (Seth Rogen). He and his hot dog brethren (inexplicably called “sausages” even though they are hot dogs and nobody in real life calls hot dogs “sausages”) sit on a display next to packages of buns, whom they lust after. Frank has his eye on a particular bun, Brenda (Kristen Wiig), and they long for the prophesied day when he’ll be slid inside of her. (Again, what happens after that is a mystery to them.) They know, however, that they must not commingle before the appointed time, or the gods will be angry.

Once they’re chosen, with honey mustard’s newfound atheism ringing in their ears and causing doubts, the story splits into three threads. In one, Frank and Brenda are removed from their packages and must traverse the supermarket in search of their home aisle, accompanied by two mortal enemies: a very Jewish bagel (Edward Norton, doing Woody Allen) and a very Arab lavash (David Krumholtz), who hate that they’ve been forced to share aisle space. (Elsewhere, a Native American bottle of “firewater” complains about his people being pushed off their shelves by “crackers” — meaning saltines and such, of course.)

Meanwhile, Frank’s malformed frankfurter friend Barry (Michael Cera) sees for himself what gruesome terrors befall his kind in the gods’ kitchens, and subsequently ends up out in the world, where he’s surrounded by corpses (i.e., discarded, half-eaten food). Finally, there’s an angry douche (Nick Kroll) — it’s not just food that’s alive, apparently, but any item sold in a grocery store — who wants revenge against Frank and Brenda for damaging his nozzle during a tragic shopping cart wreck.

That wreck, a morbidly funny “Saving Private Ryan” sequence, is where the film explicitly spells out its physical logic: not only is the food alive, but it feels pain when it’s crushed, sliced, or trampled. There is no end to the perverse delight the movie takes in exploring this idea.

On the other hand, whenever the movie bumps up against an aspect of the “food is alive” concept for which the writers cannot work out a logical explanation, they just ignore it. Similarly, when a line of dialogue needs to be funny and they can’t think of a way to phrase it that will achieve that effect, they often phrase it normally and just pepper it with obscenities, hoping that will make up the difference.

The screenplay is clever and ingenious, in other words, but only until cleverness and ingenuity stop coming easily. When it gets tricky, you can feel Rogen and company falling back on, “Eh, it’s just a stupid movie, don’t think too much about it.” The villain is weak (funny though it may be to see a douche walking around acting like, y’know, a douche), and the story’s self-referential resolution is the very definition of “the easy way out.”

But when it works, it works with dizzying, anarchic glee, making jokes at the expense of every ethnicity, nationality, religion, and sexuality that it can reasonably connect to a food item. Like “South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut” (the best R-rated cartoon ever made, by the way), “Sausage Party” is notable for being more thoughtful than you’d expect and filthier than you ever imagined possible.

B (1 hr., 29 min.; )