If there were an extraordinarily powerful six-hour miniseries about the life of Jesus, “The Passion of the Christ” would be the gripping two-hour finale. It begins with the Garden of Gethsemane and ends with his death and resurrection — a short space of time full of events that are alternately brutal, tragic and beautiful.

The film begins in climax and remains in crescendo for two hours — a gripping way to tell any story, but especially a story as emotionally weighted as this one. I was enthralled from beginning to end, despite knowing the plot already and despite some scenes being unendurable for their graphic depictions of torture. I don’t believe anyone has made a movie about Jesus that is more compelling than this one, and certainly no film released so far this year has even approached this level of artistic quality.

Directed by Mel Gibson and written by him and Benedict Fitzgerald, the film assumes the audience both knows about Jesus and believes in him; I suspect the movie would mean little to a non-Christian, as things like character development are almost entirely absent. You don’t get a sense of why Jesus was hailed as the Messiah by some and reviled by others, because the part of his ministry that would have shown that is done before the movie starts.

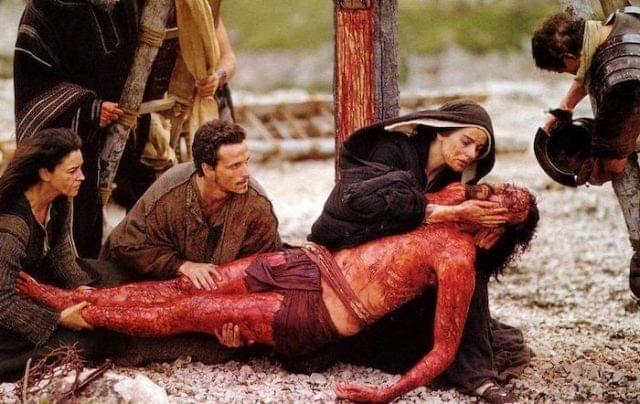

Instead, the film focuses on the end of his life, on Jesus’ flesh and blood — literally and figuratively — and both literal and figurative representations of it appear in nearly every frame. Much has been said about the violence of the film, and I’m here to tell you that those who have mentioned it weren’t just whistlin’ Dixie. The scene in which Jesus is whipped and scourged — if you do not know how the Romans did their scourging, then you are in for a shocking lesson — is one of the most harrowing moments of my movie-going life. Despite constantly telling myself, “It’s only a movie; that’s just makeup; those are special effects,” it was still often only through half-open eyes that I could watch it. (The crucifixion scene is a good deal less graphic, though still grueling in its way.)

Though I believe these events actually occurred, and that they directly affect my own spiritual welfare, I don’t think that’s why they were so difficult to watch. What made it hard to bear was the extremely realistic and relentless manner in which they were filmed. Sound effects are present but not overdone. Blood is spilled but not like the absurd geysers we see in slasher films. The cries of pain seem real as Jesus (played with heroic intensity by James Caviezel) is whipped and gouged. Even if it involved characters who were purely fictional and irrelevant, it still would have been a torturous sequence to sit through.

Since most people prefer either no violence at all, or else the stylized, cartoonish bombast of the average Hollywood blockbuster, the question is, why would you want to see something as realistically gruesome as this? Will seeing Christ’s suffering re-enacted so viscerally increase one’s faith, or be spiritually uplifting somehow? I can only tell you my experience.

As I’ve contemplated this aspect of Jesus’ life over the years, I’ve often wondered whether I had it in me to do anything even remotely as selfless. I’ve usually concluded that, if called upon to do so, I could indeed endure great physical pain for the sake of those I loved. I wouldn’t look for opportunities, of course, and I would certainly blubber endlessly about the pain involved, but I’ve generally thought that I could be stoic and brave enough to suffer immensely if it were truly necessary.

But seeing Jesus’ torment so vividly recreated — the scourging, in particular — made me rethink that position. I thought, “OK, here’s an example: Could I endure THIS specific punishment if it would, say, save my mother’s life?” And I was humbled to realize the answer was no — not because I’m a coward, or because I don’t love my mother, but because I was seeing, in graphic detail, the extreme level of sheer physical agony involved. It was no longer a nebulous, imaginary thing or a morbid “What if?” game. It was right there before me, projected in sound and color on a giant movie screen. I could barely endure the pain of watching someone else endure the pain — and it was only an actor, and his pain wasn’t real.

And this led me to think of the real Jesus, and how he actually DID endure this, and it strikes me that if his pain was even a fraction as hellish as this reenactment appeared to be, then all my life I have been far less appreciative of him than I ought to have been. The idea of Jesus taking the sins of the world upon himself is abstract to me, because I don’t know what that would feel like, or what natural force would cause one to feel it. It is spiritual, not tangible. But pain, I can relate to. The physical aspects of Christ’s atonement are something I can understand — and I understand them better, and am more grateful for them, after seeing their depiction in this film.

So that is my experience with the movie. I hope you’ll excuse the highly personal nature of all that; it’s not common to become so introspective in a movie review — but, then, it’s not common that a movie causes me to become so introspective (a fact I am rather grateful for, now that I think about it).

Because it has been discussed endlessly, I should address the allegations of the film’s anti-Semitism: The allegations are wholly without merit. Jewish leaders are indeed shown to be the ones clamoring for Jesus’ execution, but there is no underscoring, no statements to the effect of, “Hey, look what THE JEWS did!” The focus is on what happened, not who caused it. End of story.

The dialogue is in Aramaic, Hebrew and Latin, which were the languages of the day, with the addition of English subtitles, which were somewhat less common. The language was meant to lend the film realism, though to be truly effective, it would need to have been accompanied by a documentary style of filmmaking, not the highly cinematic method employed by Gibson and cinematographer Caleb Deschanel. The language is not a liability, but it is not a strength, either.

I have indicated my personal feelings about the film’s use as a religious experience, but let me return to my assertion that simply as a film, it is better than anything else released so far this year. Gibson stays faithful to his source material, but embellishes on it enough to give the narrative some structure and weight. Through judicious use of brief flashbacks, we discern Jesus’ tender relationship with his mother (Maia Morgenstern) and his role as teacher and friend to Peter (Francesco De Vito) and John (Hristo Jivkov). Mary’s agony over her son’s sacrifice is exquisitely portrayed, and Judas’ (Luca Lionello) betrayal and subsequent guilt are fantastically eerie, given a supernatural flavor that crystalizes the movie’s inherent spirituality. Hristo Naumov Shopov’s sharp performance as the morally conflicted Pontius Pilate is also worthy of note: Here is a character whose role in the story in integral, but who seldom gets the respectful, muscular portrayal he deserves.

Gibson and I may disagree on some points of doctrine, but I respect anyone who makes a film based on his personal convictions, and even more so if the filmmaker does a vigorous, handsome job of it, as Gibson has done here. Too often, artists who endeavor in “labors of love” are too swallowed up in their affinity for the thing to create something that will be of worth to anyone other than themselves. “The Passion of the Christ” is a rare thing indeed, then: a work of art that succeeds as a film, as a message, and, yes, as a labor of love.

A (2 hrs., 7 min.; in Aramaic, Hebrew and Latin with subtitles; )